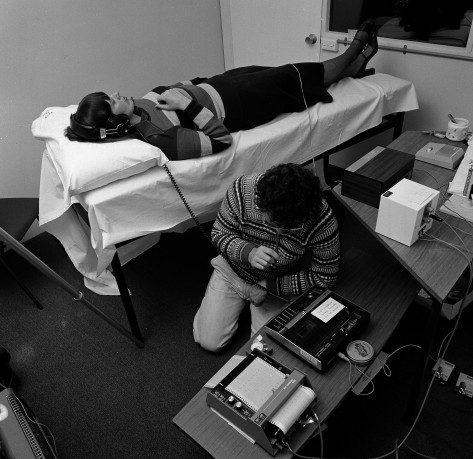

News of my book and in particular, news of the LaTrobe obedience experiments conducted by students on students in 1973 and 1974 broke a week ago in the Australian media. Newspapers, TV and radio around Australia have covered the story. And all week I’ve been worrying about the impact on the people involved.

Stanley Milgram’s shadow has cast itself over all my dealings with participants in his research – not just those from the LaTrobe study in Australia, but those I interviewed in the USA who did the original experiment at Yale fifty years ago.

Milgram argued, in response to accusations of carelessness about the wellbeing of his subjects, that he’d done his utmost to make sure no one was harmed by the experiment. He had conducted ‘careful and thorough’ debriefing with each of them before they left the lab. Even if this was true – my research found that 70% of his subjects were not debriefed at the end of the experiment – Milgram clearly saw that his obligations to the welfare of his subjects ended at the lab door.

He was not nearly so careful about their feelings in his book and in media interviews where he consistently misrepresented them as akin to Nazi concentration camp guards. On ‘60 Minutes’ in March 1974 he told presenter Morley Safer that his research showed that : ‘If a system of death camps were set up in the United States of the sort we have seen in Nazi Germany, one would be able to find sufficient personnel for those camps in any medium-sized American town.’ The media, by and large, have reproduced this depiction of Milgram’s subjects in pretty much the same way ever since.

Not surprisingly, I’m a bit sensitive to the way people I’ve interviewed are portrayed in the media. I feel very protective of the people who were unlucky enough to take part. Not just the ones I met and interviewed, but all the others who’ve carried the burden of those experiments for the past forty years. And I’ve been conscious that unearthing news of the experiments could prompt painful memories for some.

But I’ve been reassured by the number of LaTrobe alumni who’ve been in touch with me since the book came out to tell me what a relief it is to hear the experiments being aired publicly for the first time.

Of course there are many more out there. This week I was told that my original estimate of the number of students involved at LaTrobe was too low. That the total number involved during 73 and 74 was closer to 600. Whatever the final figure is, I hope that hearing others talk openly in the media about their experience, others will feel less burdened as a result.

Instead of punishing themselves about what they did or didn’t do back then, they could turn their attention to the motivations of the organizers of an undergraduate program who felt that conducting such a potentially destructive and unethical experiment was a necessary part of psychological training.